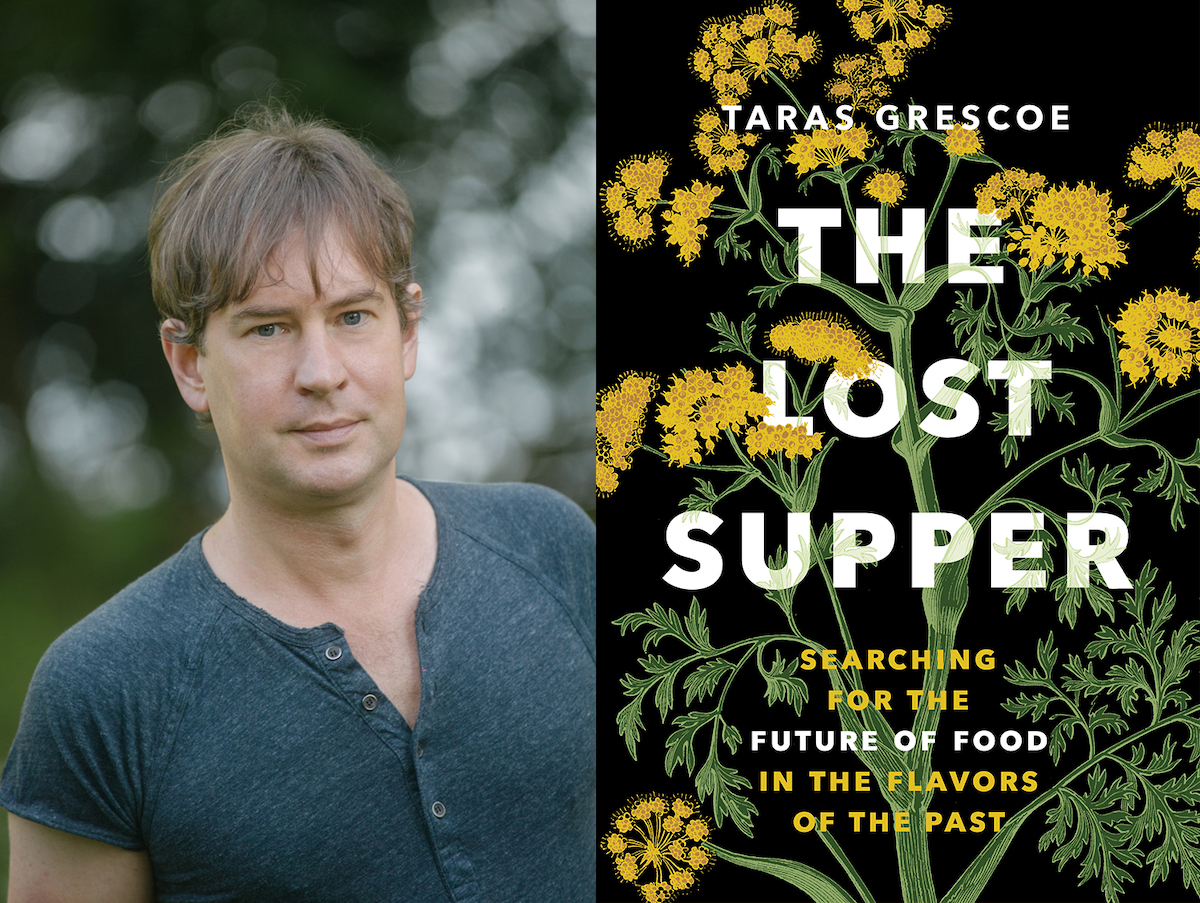

[Editor’s note: ‘The Lost Supper: Searching for the Future of Food in the Flavors of the Past’ is a globe-trotting exploration of foods lost and near-lost to modernity — and recent efforts to revive these foods.

In this excerpt, Taras Grescoe explores the near-lost art of English farmhouse cheese — made on the farm site where the cows are raised and milked — arguing that rather than doing away with animal agriculture, we should be looking to foodways of the past to rediversify, transitioning away from industrial agriculture and back to smaller, more sustainable farms.]

In Europe, cheese is never just cheese. It is a symbol of place, of soil, of terroir. In France, even the most rubbery, pasteurized, processed supermarket brand of Camembert trades on its ties to the Norman countryside and the enduring gloire of peasant traditions.

In the culture wars surrounding Brexit, Conservatives and Leavers held up “territorial” cheeses as examples of the sturdy, traditional products of a mythical Great Britain that, once purged of Continental influence and competition, would once again flourish. Some environmentalists, meanwhile, vilify cheese — along with liquid milk, factory farms and veal-fattening pens — as a symbol of a Dairy-Industrial Complex responsible for animal cruelty, climate change and the monocultures hastening the loss of biodiversity.

Guardian journalist George Monbiot, the main proponent of the latter view, believes that raising livestock for food is an abomination. In his documentary Apocalypse Cow, the vegan activist argued that the British Isles should be “rewilded,” and wildlife allowed to roam free through forests, marshes and grasslands as they re-emerged from fields and pastures liberated of farms. The human population, cleared from the land into cities, could subsist on almond milk and artificial protein.

To make his case, Monbiot flew to Helsinki to sample a grey pancake synthesized in a lab from oats and bacteria. “That is lovely,” he declared for the camera, adding, none too convincingly, “I would eat that every morning.”

Left out of the picture, or at best reduced to caricatures in condescending media profiles, are Britain’s cheese farmers (the term of art for makers of farmhouse cheese), who, being human, are confoundingly complex in their backgrounds and political outlooks. Charles Martell, responsible for reviving Gloucester cheese in the 1970s, declared himself an ardent supporter of Brexit, much to the delight of the European press, who noted that his wife was Ukrainian and his territorial cheese was made with the labour of Polish and Romanian farmhands.

Meanwhile, the only maker of authentic raw-milk Stilton in Britain, which is retailed as Stichelton — the Old English name for the eponymous Sherwood Forest village — is a transplant from upstate New York named Joe Schneider.

My next stop was the warehouse of Neal’s Yard Dairy in Bermondsey, where chief buyer Bronwen Percival greeted me with a wide-open Californian smile. She grew up in San Diego County, where her family kept goats on a small acreage in the Cuyamaca Mountains. Percival’s book Reinventing the Wheel, which she co-authored with her husband, Francis, is the best account I’ve read of why seeking out and enjoying farmhouse cheese is a form of resistance to the uniformity brought by industrial agriculture.

Percival showed me around the offices and storage areas of Neal’s Yard Dairy’s warehouse, located in a viaduct beneath the tracks of the London and Greenwich Railway, one of the world’s first passenger railways. “It’s nice to have brick arches,” she said, “because they’re fairly well insulated and keep the cheese cool in the summer.”

After we’d put on smocks and hairnets, she took me on a tour of a turophile’s paradise. In four of the railway arches, wooden shelves were stacked to the ceiling with big cylindrical truckles of Westcombe, Hafod, Cheshire and Wensleydale. I told her the abundance of cheeses in Neal’s Yard Dairy was the exact opposite of Monty Python’s Cheese Shop sketch.

“Well, that was a pretty accurate depiction of a land bereft of cheese,” said Percival, with a laugh. When the original Covent Garden shop opened in 1979, owners Nick Saunders and Randolph Hodgson first focused on making their own dairy products, but they soon struck out from London to establish contacts with farmhouse cheesemakers.

The problem was, Percival pointed out, there were very few left. “The extinction had already taken place. There were a few vestigial producers who were making a handful of Cheddars, Cheshires and Lancashires, but people had stopped making farmhouse cheeses in favour of selling liquid milk, which they could get a guaranteed price for.”

In their book, the Percivals document how the industrialization of dairying wiped out diversity on every level, from the microbes in milk to the grasses and wildflowers in pastures to the livestock breeds in farms and finally to the richness of human communities in rural areas. Before the 19th century, a fantastic variety of cheeses, of varying quality, were made on small farms. All of them were coagulated with rennet, usually obtained from the stomach of a cow, goat or sheep, and fermented with the microbes naturally present in the whey from earlier batches, in the raw milk itself, or even in the cracks and crannies of pails, wooden shelves and old stone walls.

The coming of the first railways — like the ones conveying the trains rumbling over our heads at Neal’s Yard — in the 1830s allowed liquid milk to be brought to cities. Together with canals and turnpikes, railways helped fashion a distinctive British cheese: low in moisture, high in acidity and, above all, hard — qualities that made cheeses easy to transport, especially when shipped as large truckles, like the barrel-shaped Stiltons, Cheshires and Cheddars stacked on the warehouse shelves around us.

The industrialization of cheesemaking

Cheesemaking was first industrialized on the other side of the Atlantic. Jesse Williams, a farmer with 65 cows who wanted to process the milk from his son’s farm, opened the first true cheese factory in Rome, New York, in 1851; within 13 years, there were over 200 such cheese factories in New York state alone. Factory Cheddar from the New World, wrapped in cloth for transport, began to arrive at the port of Bristol to be shipped by rail to London, where it retailed for half the price of authentic British Cheddar.

Two scientific breakthroughs contributed to the gradual extinction of farmhouse cheesemaking. Chemist Louis Pasteur’s process for killing pathogens in wine through rapid heating was applied to liquid milk in the 1880s, as an attempt to end the scourge of tuberculosis. The Danes used pasteurization to kill the spoilage bacteria in cream, which they then fermented and exported to Britain in the form of a cheap, stable, mild-flavoured butter. When the same process was applied to raw milk, it wiped out pathogens but also killed the beneficial bacteria necessary to ferment the milk into cheese.

A Danish chemist named Christian Hansen, who had already developed a purified extract to replace rennet, founded the company that offered a solution: to the blank slate of heat-purified milk, cheesemakers could add a few chemically isolated strains of lactic acid bacteria. Prepackaged sachets of starter culture did for the world of cheese what Fleischmann’s powdered yeast did to sourdough bread: it eliminated a fantastic range of diverse flavours. (Another maker of starter cultures, DuPont, boasts that every third cheese currently made in the world uses its Danisco range.) According to the Percivals, the combined impact of pasteurization, starter cultures and obsessive hygiene has led to what they call a “holocaust” of raw-milk microbes.

“This is not a term that we use lightly,” they wrote in Reinventing the Wheel. “The quest for control has caused the catastrophic destruction of the microbial communities on which cheesemakers rely to make their raw-milk cheeses distinctive.”

Bronwen Percival believes this lost diversity extends to our gut. Before pasteurization, the bacterium Helicobacter pylori, whose presence may have a beneficial impact on the immune response, was found in just about everybody’s gut; now it’s present in the stomachs of fewer than six per cent of young Americans, and its absence has been linked to a rise in allergies and asthma. “The jury’s still out, but I think it’s a plausible hypothesis that by putting a diversity of microbes into our digestive tract, we’re stimulating our immune systems in ways that have all kinds of notable health effects.”

In Britain, the near-disappearance of farmhouse cheeses is only partly explained by the rise of factories, pasteurization and starter cultures. In 1933, the Milk Marketing Board was set up to stabilize the price of liquid milk. During the Second World War, all farmers were forced to sell their milk to the board, and factories were limited to making Cheddar and a few other varieties of strictly rationed cheese.

Before the war, there were 1,000 registered producers of farmhouse cheese, a third of them making Cheddar; by the time rationing ended, in 1954, just 140 farmhouse cheesemakers remained. France also experienced prewar industrialization — by the 1890s, Camembert was already a mass-produced, mass-marketed product, designed for rail shipments from Normandy to Paris — but the French didn’t nationalize their milk supply during the war. Today, there are just 350 artisanal cheesemakers in the United Kingdom, only a few dozen of them true farmhouse producers, compared to 4,500 in France.

About as sustainable and ethical as farming gets

The truth is that farmhouse production accounts for a vanishingly small percentage of the cheese consumed around the world.

Since 1997, 40-pound blocks of Cheddar have been traded, along with wood pulp and pork bellies, as commodities on the floor of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange. In the past, the standard family farm had a dozen or so cows, with breeds adapted to the climate and landscape; today the largest factory farms in California have single-breed herds of 19,000 animals. And, of course, while the milk we get comes from lactating cows, goats and sheep, most of their offspring are slaughtered and eaten.

As cheesemonger Ned Palmer, a former employee of Neal’s Yard Dairy, wrote, “The hard fact is that if you consume dairy products you are to some extent involved in the death of animals. Calves, lambs and kids are, to put it bluntly, surplus to requirements in a dairy herd unless they are needed to replace a milking animal that has retired.”

Percival knew all this, yet still passionately stood by the idea that good cheese is worth not only fighting for but also paying for. “The charge of elitism comes up all the time. But I believe that’s because there’s been a debasement of this very precious food.” In the 19th century, she pointed out, people paid a high price for Cheddar and other cheeses relative to what they earned.

“I’m not saying we should go back to that, but we should recognize that the dairy industry has become hugely extractive, and inflicts a lot of hidden costs on the environment. As a society, we should be eating a lot less animal protein, whether it’s cheese or meat. What we do eat has to be sustainably produced. And yes, that’s going to be more expensive.”

Farmhouse cheese is about as sustainable and ethical as farming gets. It’s also, in my opinion, one of the most life-enriching foods you can eat. In this way, raw-milk cheese is like dark chocolate, vintage wine or homemade sourdough bread: you don’t need a lot to feel deeply, lastingly satisfied.

I asked Percival what she thought of George Monbiot’s idea that agriculture itself was the culprit, and allowing farmland to revert to nature was the best way to heal the planet.

“So we’ll all survive on yeast extract or something?” she scoffed. “He believes the only truly valuable biodiversity is completely natural. And biodiversity that’s man-made, or partly man-made, has no value whatsoever.”

The best response to that, she said, was to pay a visit to a farmer who was making territorial cheeses in a non-industrial, traditional way. “You’ll see seminatural landscapes, meadows and pastures that are incredibly biodiverse. Along with cows, they support wildflowers, insects, animals, all kinds of ground-nesting birds that wouldn’t survive in a forest.”

But I was way ahead of her. My next destination was the original home of the legendary cheese of Wensleydale. My train was leaving in an hour.

Adapted with permission of the publisher from the book ‘The Lost Supper: Searching for the Future of Food in the Flavors of the Past,’ written by Taras Grescoe and published by Greystone Books in September 2023. Available wherever fine books are sold. ![]()

To Fix Agriculture, Eat More Farmhouse Cheese - TheTyee.ca

Read More

No comments:

Post a Comment